INTRODUCTION

Alveolar echinococcosis (AE) is a larval tapeworm infection that occurs in humans after ingestion of foods contaminated with the larval form of Echinococcus multilocularis. AE is one of the most dangerous zoonotic diseases in the world. AE most commonly invades the liver and by acting like a malignant neoplasm in the tissue, it leads to invasive and destructive changes. AE rarely causes Budd-Chiari syndrome (BCS) as a result of occlusion of the hepatic veins and inferior vena cava [1,2]. In this paper, we report a case of AE associated with BCS in Turkey.

CASE DESCRIPTION

A 62-year-old female patient admitted to our clinic because of recent fatigue, shortness of breath, abdominal distention, and pain in the right upper quadrant. In her history, she had a liver wedge resection 3 years ago with AE found in the biopsy material. On physical examination, the liver was 5 cm palpable under the right rib, the spleen was non-palpable, and Traube's space was clear. Tension ascites and collateral veins in an upward flow direction were noted on the abdomen. Respiratory sounds were decreased at the bases of both lungs and dullness was found with percussion.

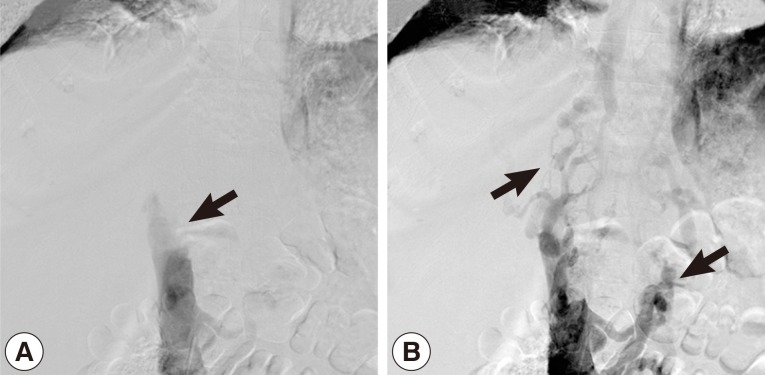

Hemoglobin was 8.3 g/dl in the whole blood count. Except for low albumin levels (2.1 g/dl), all other biochemical tests were normal. There was no flow viewed in the left hepatic vein and inferior vena cava on abdominal portal Doppler ultrasound. The portal vein was 16 mm, and the splenic vein was 15 mm in diameter and hepatofugal flow was noted. On contrasted abdominal CT, there was a 54×70×45 mm-sized cystic lesion in left lobe of the liver extending towards the posterior mediastinum with irregular calcifications that invaded the diaphragm, esophagus, and pericardium. It was occluding the inferior vena cava and left hepatic vein at the level where the hepatic veins poured into the inferior vena cava. Secondary to inferior vena cava occlusion, the azygos vein and the hemiazygos vein appeared to be dilated. There was bilateral pleural effusion (Fig. 1A, B). A grade 1 esophageal varix was observed on upper endoscopy. The inferior vena cava was found to be occluded at the L1 level with venography. It was determined that the venous return was provided by the azygos, hemiazygos system, and the collaterals (Fig. 2A, B). In the performed echocardiography, the entrance of the inferior vena cava into the right atrium was normal.

With paracenthesis, the intraperitoneal fluid was turbid and total leucocyte number was 410/mm3 (10% neutrophils, 90% lymphomonocytes). The intraperitoneal fluid was exudate in character (serum acid albumin gradient was 0.2 g/dl) and protein was 5.1 g/dl. There was no other pathology found in the Gram staining and culture of the intraperitoneal fluid.

According to these findings, the patient was diagnosed with secondary Budd-Chiari Syndrome (BCS) development due to AE. The patient was given 15 mg/kg albendazole (800 mg/day) for treatment.

DISCUSSION

BCS develops as a result of occlusion of the venous system at any location from the small veins to the junction of the inferior vena cava at the right atrium. This occlusion may be due to primary or secondary reasons. Primary reasons mostly include hypercoagulopathy disorders. Secondary reasons are a result of intraluminal invasion or extraluminal compression [3,4]. In our case, secondary BCS developed due to both intraluminal invasion and extraluminal compression of the suprahepatic inferior vena cava and left hepatic vein. Patients with hepatic hydatid cyst, size and posterior localization of the cyst, invasion of 2 or more segments, and prior surgery or infection are the predisposing factors for development of BCS [4]. In our case, most of the predisposing factors were present.

In a large scale survey conducted with 362 AE cases, BCS rates due to inferior vena cava invasion was reported to be approximately 1.8%. In another study, in BCS patients there were about 25% acute and 75% subacute clinical findings. The predominant symptom was found to be right upper quadrant abdominal pain [4,5]. In our patient, the clinical findings had a subacute chronic course, and the predominant symptom was right upper quadrant abdominal pain.

Current treatments have substantially improved the prognosis of AE patients [6]. However, early diagnosis is important for morbidity and mortality. AE generally remains asymptomatic for 5-10 years and later displays a chronic course. In cases that are not treated or insufficiently treated, mortality rates increase. After a diagnosis, a 5-year mortality rate of the disease is 70%, and a 10-year mortality is 94%. When BCS develops, 1-year mortality is 70%, and 3-year mortality is 90% [7]. Our patient's life expectancy may be shortened due to the metastatic nature of the disease and the late initiation of treatment after surgery.

The treatment of BCS is medical and surgical. For chemotherapy, albendazole 10-15 mg/kg (in 2 divided doses) or alternatively mebendazole 40-50 mg/kg (in 3 divided doses) is used. Surgery is required for cases where BCS has developed. Other interventional methods (stent placing and angioplasty) or liver transplantation along with vena cava resection can be performed for BCS [7]. Kawamura et al. [8] have obtained good outcomes in advanced cases such as secondary BCS due to AE with chemotherapy followed by surgery. In a case report of the liver hudatid cyst with caval involvement, a combination of hepatic lobectomy and vena cava resection was reported to be successful. In disseminated abdominal hydatidoses, long-term chemotherapy reduces the incidence of recurrence and mortality [9,10].

In conclusion, AE is among the most dangerous zoonotic diseases in the world. In recent years, its frequency has increasing due to transmission of the disease from dogs to humans. In AE disease, the liver is the most commonly invaded organ and due to dissemination of surrounding structures, lymphatic and vessels, it mimics malignant neoplasms. AE is a serious cause of morbidity and mortality. As in our patient, AE can invade the hepatic veins and inferior vena cava leading to BCS. In patients that apply to clinics with BCS, AE, although rare, should be considered among the etiological causes.